Ty i Ja was first published in 1959 by the Women's League, an offshoot of the official Polish United Workers’ Party run by helmet-haired party harridans. Early on, however, it was hyacked by a group of young writers and designers. This was not as strange as it sounds. In the command economy — where a central planning office determined the amounts of buildings, books and spoons required by society - quantity always prevailed over quality. What mattered - at least at first — was how many magazines were available, not what was being said on their pages. After all, Ty i Ja was “ just” a women’s magazine.

In the hands of editor Roman Jurys, the magazine was turned into a remarkable vehicle for the popular discussion of modern life in all its dimensions. In the early 1960s, an issue might contain an earnest discussion by a psychologist on the unhappy state of marriage side-by-side with a photo-spread on erotic sculpture ornamenting Indian temples. [...]

Ty i Ja’s contributors struck a strange balance between fascination with the spectacle of the consumer society and tts critique. This was in fact the position of many Polish intellectuals in the 1960s: left wing by inchnation and by intellectual formation, they were, nevertheless, attracted to the forbidden pleasures of the consumer society. [...]

Ty i Ja — with its serious minded rhetoric and its fantasy — might be characterized as incoherent. Yet it was not. Perhaps Foucault's idea of the heterotopia can explain why. In heterotopia, unusual and heterogeneous things can exist side-by-side without one claiming special status over the others. On the pages of Ty i Ja, hwerarchy gave way to lateral relations. This order of things can, according to Foucault, produce “ an almost magical uncertain space ” and “ monstrous combinations that unsettle the flow of discourse. ” Whilst this concept is usually understood in spatial terms, he suggested it could also be applied to describe writing that makes “ impossible ” discursive statements or challenges.

What was “ possible ” in socialist Poland was, of course, predetermined by a historical script written by the Party. Viewed from this context, a magazine which eschewed inscribed social hierarchies and embraced uncertainty could, it seems, be “ an almost magical space. ”

Not explicitly political, Ty i Ja took an interest in what had been rendered other or illicit by peevish minds in the Central Committee.

– " Applied Fantastic, ” David Crowley, Dot Dot Dot 49, 200%

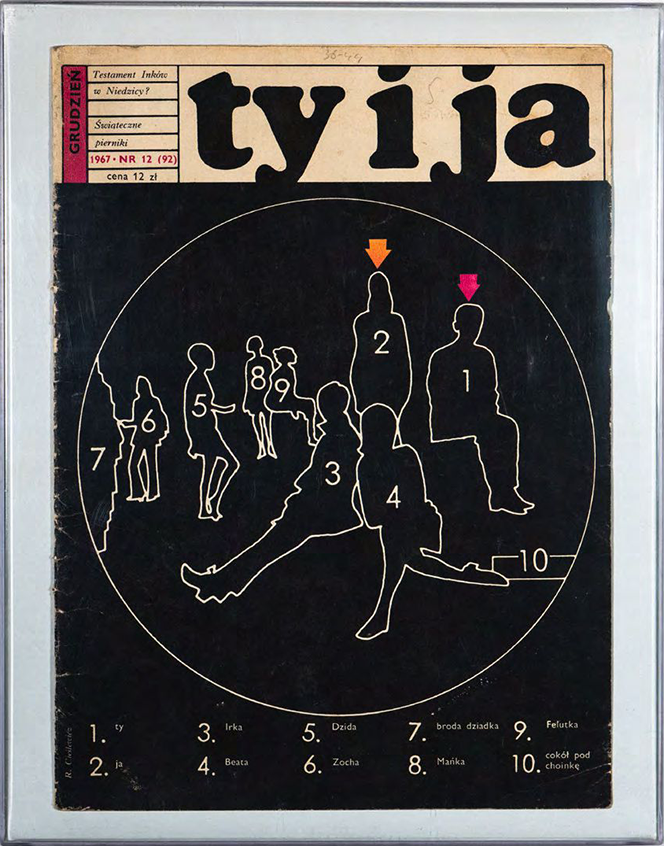

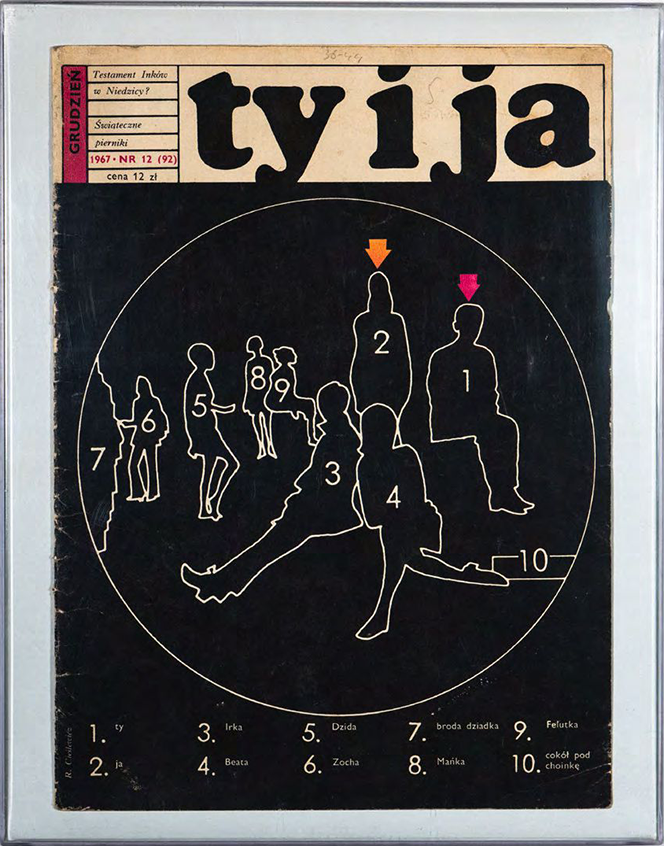

No. 12 (92), Ty i ja magazine, 1967, 35.8 x 28.5 cm