USELESS

ARCHI

TECTURE

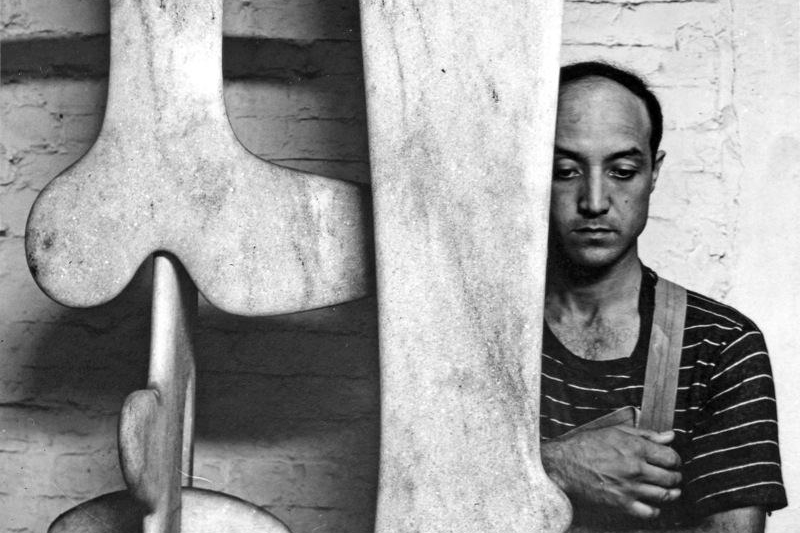

Isamu Noguchi

Held from may 19, 2021 to may 8, 2022, Noguchi: Useless Architecture is an exhibition of around fifty works mostly drawn from the Noguchi Museum’s collection and occupying its second floor galleries. In 1949 and again in 1960, Isamu Noguchi visited India’s Jantar Mantar in Delhi and Jaipur, two of the original five campuses of astronomical devices created on a grand architectural scale by the 18th-century Maharaja Jai Singh II. Noguchi described the conglomeration of instruments at each site—so large as to be more recognizable as monumental sculpture or architecture than as functioning devices—as “useless architecture, useful sculpture.” The exhibition was directly inspired by this phrase.

The genie

of the lamp

Isamu Noguchi (1904–1988) was one of the twentieth century’s most important and critically acclaimed sculptors. Through a lifetime of artistic experimentation, he created sculptures, gardens, furniture and lighting designs, ceramics, architecture, and set designs. His work, at once subtle and bold, traditional and modern, set a new standard for the reintegration of the arts.

Noguchi, an internationalist, traveled extensively throughout his life. (In his later years he maintained studios both in Japan and New York.) He discovered the impact of large-scale public works in Mexico, earthy ceramics and tranquil gardens in Japan, subtle ink-brush techniques in China, and the purity of marble in Italy. He incorporated all of these impressions into his work, which utilized a wide range of materials, including stainless steel, marble, cast iron, balsa wood, bronze, sheet aluminum, basalt, granite, and water.

When Noguchi’s mother Léonie Gilmour met his father, she was a young writer and editor living in New York City. Gilmour was a white American of mostly Irish descent born in Brooklyn. His father Yonejiro Noguchi, an itinerant Japanese poet, was Asian. Noguchi was born in Los Angeles, but moved to Japan with his mother at the age of two and lived there until the age of thirteen. In the summer of 1918, Noguchi returned alone to the United States to attend high school in Rolling Prairie and then La Porte, Indiana, adding yet another layer to an increasingly complex identity. (He proudly identified as a “Hoosier” for the rest of his life.)

After high school he moved to Connecticut to work briefly for the sculptor Gutzon Borglum, and then to New York City to attend Columbia University. While enrolled there as a premedical student, he also began taking evening sculpture classes on New York’s Lower East Side with the sculptor Onorio Ruotolo at the Leonardo da Vinci School of Art. He soon left the university to become an academic sculptor, supporting himself by making his first portrait busts.

In 1926, Noguchi saw an exhibition in New York of the work of Constantin Brancusi that profoundly changed his artistic direction. With a John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship, Noguchi went to Paris, and in 1927 worked in Brancusi’s studio. Inspired by the older artist’s forms and philosophy, Noguchi turned to modernism and abstraction, infusing his highly finished pieces with a lyrical and emotional expressiveness, and with an aura of mystery.

Returning to New York City as well as traveling extensively in Asia, Mexico, and Europe in the late 1920s through the 1930s, Noguchi survived on portrait sculpture and design commissions, proposed landscape works and playgrounds, and intersected and engaged in collaborations with a wide range of luminaries. Noguchi’s work was not well-known in the United States until 1940, when he completed a large-scale sculpture symbolizing the freedom of the press, which was commissioned in 1938 for the Associated Press Building in Rockefeller Center, New York City. This was the first of what would eventually become numerous celebrated public works worldwide, ranging from playgrounds to plazas, gardens to fountains, all reflecting his belief in the social significance of sculpture.

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and the backlash against Japanese Americans in the United States had a dramatic personal effect on Noguchi, motivating him to become a political activist. In 1942, he cofounded Nisei Writers and Artists Mobilization for Democracy, a group dedicated to raising awareness of the patriotism of Japanese Americans; and voluntarily entered the Colorado River Relocation Center (Poston) incarceration camp in Arizona where he remained for six months.

Following his release, Noguchi set up a studio at 33 MacDougal Alley in Greenwich Village, New York City, where he returned to stone sculpture as well as prolific explorations of new materials and methods. His ideas and feelings are reflected in his works of that period, particularly the delicate slab sculptures included in the 1946 exhibition Fourteen Americans at The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Noguchi did not belong to any particular movement, but collaborated with artists working in a range of disciplines and schools. He created stage sets as early as 1935 for Martha Graham, beginning a lifelong collaboration; as well as for Merce Cunningham, Erick Hawkins, and George Balanchine and composer John Cage. In the 1960s, Noguchi began working with stone carver Masatoshi Izumi on the island of Shikoku, Japan; a collaboration that would also continue for the rest of his life. From 1961 to 1966, he worked on a playground design with the architect Louis Kahn.

Whenever given the opportunity to venture into the mass-production of his designs, Noguchi seized it. In 1937, he designed a Bakelite intercom for the Zenith Radio Corporation, and in 1947, his glass-topped table was produced by Herman Miller. This design and others—such as his designs for Akari light sculptures which were initially developed in 1951 using traditional Japanese materials—are still being produced today.

Noguchi’s first retrospective in the United States was in 1968, at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City. In 1986, he represented the United States at the Venice Biennale. Noguchi received the Edward MacDowell Medal for Outstanding Lifetime Contribution to the Arts in 1982; the Kyoto Prize in Arts in 1986; the National Medal of Arts in 1987; and the Order of the Sacred Treasure from the Japanese government in 1988. He died in New York City in 1988.

The mu

seum

In 1985, Noguchi opened The Isamu Noguchi Garden Museum (now known as The Noguchi Museum), in Long Island City, New York. The Museum, established and designed by the artist, marked the culmination of his commitment to public spaces. Located in a 1920s industrial building across the street from where the artist had established a studio in 1960, it has a serene outdoor sculpture garden, and many galleries that display Noguchi’s work, along with photographs, drawings, and models from his career. He also indicated that his studio in Mure, Japan, be preserved to inspire artists and scholars; a wish that was fulfilled with the opening of the Isamu Noguchi Garden Museum Japan in 1999.

In 1999, the Foundation Board approved a $13.5 million capital master plan to address structural concerns, ADA and NYC Building Code compliance and create a new public education facility. During renovation, the Museum relocated to a temporary space in Sunnyside, Queens, and held several thematic exhibitions of Noguchi's work. In February 2004, the museum was formally chartered as a museum, and granted 501(c)(3) public charity status. The Noguchi Museum reopened to the public at its newly renovated space in June 2004. The museum building continued to suffer from structural issues into the early 2000s and a second $8 million stabilization project was begun in September 2008.

There are 12 galleries and a gift shop within the museum.

Useless Archi

tecture...

“Jai Singh’s structures are mystical sculptures that define space,” Isamu Noguchi is quoted in a brief essay accompanying his photographs of the Jantar Mantar in “Astronomical City,” Portfolio: A Magazine for the Graphic Arts, 1, no. 3 (1951): 115. “You might call them useless architecture or useful sculpture. They imply a use—much sculpture does that. Whether or not they were intended so, Jai Singh’s works have turned out to be an expression of wanting to be one with the universe. They contain an appreciation of measured time and the shortness of life and the vastness of the universe.”

In this context, the phrase “useless architecture, useful sculpture” represents an alternative to an architecture that is alienating in its totalitarian self-containment, and to sculpture irrelevant to life and time’s passage. It speaks to Noguchi’s ambition to sculpt spaces free from the specific responsibilities of architecture and to create sculptures imbued with more than purely theoretical, aesthetic purpose.

...

Useful Sculp

ture.

Arranged in thematic installations – Ruins, Theater Space, Architectural Metaphors, Terraces and Panorama, Postmodern Akari, Ends – the exhibition explores how Noguchi drew on architecture to supercharge his efforts to make sculpture civic, communal, and environmental. He had a contentious but phenomenally productive relationship with architects and architecture (see, for example, the digital feature Ten Architects). He stated in an interview in 1957, “I always prefer gardens, because I can work there without pressure from anyone. You know how selfishly architects claim the most important role in a building project for themselves. They see our contribution as secondary and they limit our freedom. Which is why landscaping a garden is a solution of sorts.” (Catherine Frantzeskakis, “The American-Japanese sculptor Isamu Noguchi talks about Greece,” Zygos no. 17 [March 1957], 20.) Focusing on often overlooked public spaces adjacent to architecture such as courtyards, patios, atria, and landscaping, he was able to create timeless, humanistic spaces in a way that would not have been possible had he needed to assume architecture’s programmatic responsibilities.

Ruins are an archetype of useless architecture because they retain their associations with the making of civilization, and the suggestion of space shaping, while having shed their actual functions. The Greek temple complex at Delphi is evoked in this installation in an agglomeration of semi-ruins, composed of abstract sculptures such as Ziggurat (c. 1968), Wrapped Figure (1962), Sentry (1958), and Small Torso (1958–62). The centerpiece of the installation, Capital (1939), on loan from The Museum of Modern Art, suggests a vision of what a truly modern order of architecture might look like if developed in the manner of the classical orders represented by Ionic, Doric, and Corinthian capitals. Describing his first visit to Delphi, Noguchi wrote: “To trace the white marble remnants, imagining their use from scanty information: that I take [it] is what imagination is for. All was there to be filled in as we chose.” On a return visit to Greece on his honeymoon, Noguchi photographed his wife Yoshiko “Shirley” Yamaguchi at the Acropolis in Athens in front of the Erechtheion as a caryatid.

Noguchi’s first design for Martha Graham, for her ballet Frontier (1935), employed a single length of rope to “throw the entire volume of air straight over the heads of the audience” (Isamu Noguchi: A Sculptor’s World: 125) and create “an outburst into space and at the same time an influx toward infinity.” (The Isamu Noguchi Garden Museum: 212). In all subsequent sets for Graham—who wanted structure not scenery—Noguchi distilled environments into objects in order to create imaginary spaces. In Seraphic Dialogue (1955) he captured the whole majesty of France in a simple drawing of Chartres cathedral in space, while Embattled Garden (1958) both literalizes and analogizes life in and outside the precinct of Eden.

Noguchi did not believe that it was the job of sculpture to decorate buildings. But he was extremely interested in deconstructing and appropriating the strategies and techniques through which architecture wielded its space-making, space-defining authority. In these columns, lintels, beams, peaks, and parts, Noguchi explores materials, structural systems, and architectural features almost as an architecture studio would in doing the basic research required to prepare for a major building project. He also expands the architectonic palette by returning, as in Triple Nest (1979), to nature, the “better craftsman.” The implications this may have for rethinking how we define and delineate human-made environments is seen perhaps most dynamically in Costume for a Stone (1982), in which a rock appears to climb through a freestanding window.

Terraces were one of Noguchi’s simplest and most powerful semi-architectural play concepts. (All they do is to change your perspective!) One of the most interesting ways in which sculpture can be said to outstrip architecture is by working with human scale without having to adhere to or serve it functionally—as it does in the context of a playground. The human-scale terracing presented here was excerpted from a playground maquette for Riverside Drive (c. 1961), an unbuilt project Noguchi pursued between 1961 and 1965 with the architect Louis Kahn. These simple changes in level enable an altered view of two panoramas composed of various architecture-adjacent ideas of Noguchi’s.

For Isamu Noguchi’s Space of Akari and Stone at Yurakucho Art Forum, Tokyo (organized by the Seibu Museum) in 1985, collaborating architect Arata Isozaki worked from a cryptic poem that Noguchi gave him to inspire and guide a series of material, scale, and conceptual contrasts. Isozaki emphasized the softness of Akari, as well as their almost boundless capacity to humanize an environment, by juxtaposing them with chain link fencing and corrugated steel. Variations on some of Isozaki’s concepts (a banquette, a cage, and a puppet theater-like enclosure), while useless architecturally, demonstrate just how much Akari can do to organize and naturalize the space around them.

Temporarily relocated from the garden, End Pieces (1974) is a room that cannot be opened or entered: installed here in another room as what Noguchi would have called a “space of the mind.” What’s inside is a secret.

Ressources

Noguchi: Useless Architecture is supported, in part, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, in partnership with the City Council and by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo and the New York State Legislature.